Episode 32. Mitchell Froom

The opening music in this episode is the exquisite and mesmerizing title track from Mitchell Froom’s new full-length album Ether featuring spectral keyboard performances plus several guest vocalists.

June 5th, 2019

Santa Monica

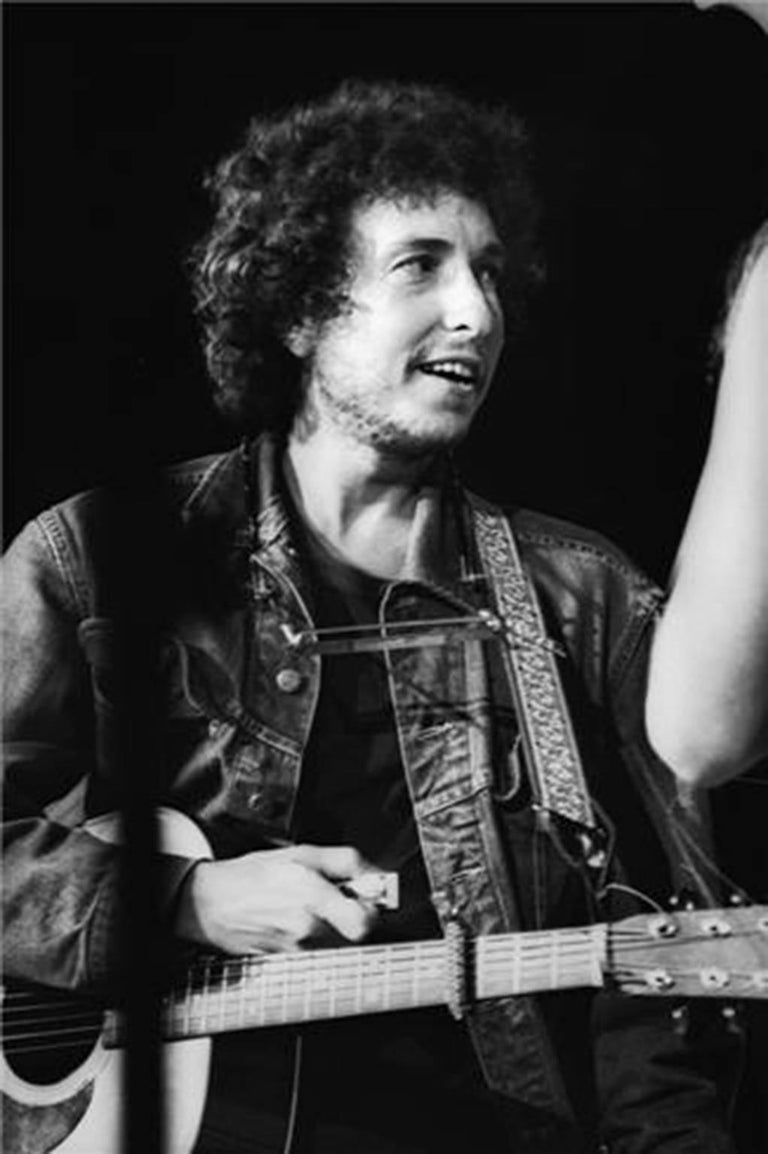

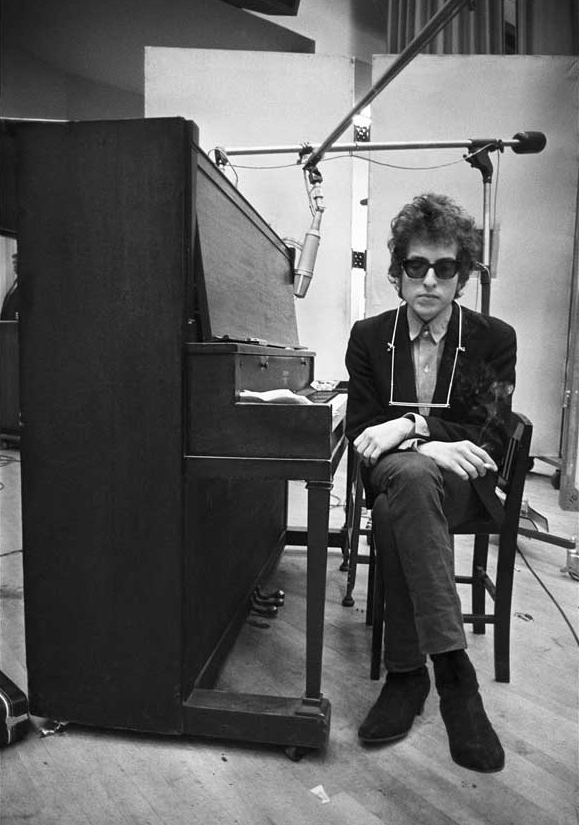

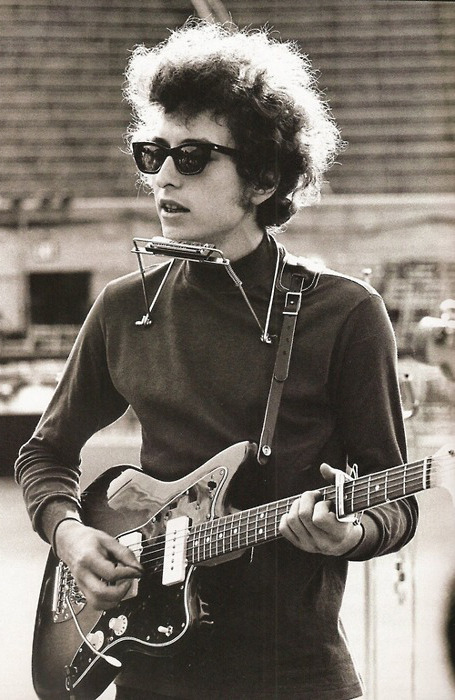

Top Photo by Paul Zollo

This year also saw the release of Monkeytree , an EP of fiercely adventurous studio wizardry co-created with Froom’s current recording partner and engineer, David Boucher.

Photo by Paul Zollo

June 5th, 2019

with mellotrons

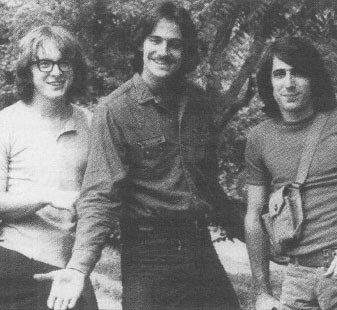

The Latin Playboys – left counter-clockwise (Mitchell Froom, David Hidalgo, Louie Pérez, Tchad Blake)

Froom & Rufus Wainwright at United Studios

Mitchell Froom and Paul Zollo, June 5th

Mitchell Froom and Paul Zollo, June 5th

(in Mitchell’s Santa Monica studio)

photo by Louise Goffin

“Projects like these tend to do two things,” says Froom, who has demonstrated a streak of sonic audacity throughout his career as member of the Latin Playboys and with his solo albums, The Key of Cool (1984), Dopamine (1998) with Suzanne Vega, David Hidalgo and other featured singers and A Thousand Days (2004), a collection of bittersweet solo-piano reveries. “One is in simply trying to push myself to come up with something that’s unique unto itself, however good or bad the results may be. The other is in developing some new techniques that I can use in different ways on other people’s music.”

Since the mid-1980s, Froom has produced more than 100 albums, with sales in excess of 50 million units. His c.v. boasts deeply collaborative relationships with some of the most important and influential artists in modern music, and many of them—like Randy Newman, Elvis Costello, Bonnie Raitt, Richard Thompson, Los Lobos and Crowded House —have looked to Froom as a go-to producer and arranger for multi-album runs. Indeed, to list Froom’s production credits is to risk résumé overkill, but so it goes: Paul McCartney, Fleetwood Mac, Rufus Wainwright, Sheryl Crow, Indigo Girls, Suzanne Vega, American Music Club, Ron Sexsmith and on and on. As a session musician or arranger, he’s appeared on albums by Bob Dylan, Tom Waits, David Byrne, Pearl Jam, Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers, Janet Jackson, Laurie Anderson and many others.

“The idea for Monkeytree was to see how far we could push things around, making the music sound confrontational and fun but compositional at the same time,” says Froom, who used vintage synthesizers under the sway of DJ culture-projects he and Boucher have been hearing. “I’m always interested in trying to push the limits of the recording studio in different ways.” Other musicians on the EP include guitarist Val McCallum, bassist Davey Faragher and drummer Matt Chamberlain.

Ether, like Monkeytree, was recorded in Froom’s Los Angeles by overdubbing analog synthesizers—Mellotrons, Chamberlins and more—with a focus that bordered on obsession. The average composition on the album, Froom says, could have 60 tracks, and much of these outsized musical landscapes were completed by recording one note at a time and then expertly manipulating that note, in the process inventing techniques to give the layered synths a more vibrant, tangible presence. “I’d get five seconds of music a day, if I was lucky,” Froom laughs. “Sometimes I’d have to throw it away, which was really depressing.”

The album’s five original instrumentals – “Pipe Dreams,” “Black Night Blues,” “Some Smoke,” “Aquarium” and the title track – are like gorgeously haunting dispatches from the Space Age. “I wanted to mix it up and have it sound sort of futuristic, but in a ’60s way,” Froom says. His melodies harbor the melancholy beauty of Tin Pan Alley gems that never were, and his lush arrangements are orchestral in scope while retaining the idiomatic qualities of keyboard performance. “To me it sounds like this very elaborate theatre organ that somebody is managing to play,” he explains.

Ether features five beloved singers he’s recorded in recent years. The fast-rising singer-songwriter Pete Molinari offers the wistful “Cold Misty Blue,” with Froom’s synths providing the requisite pedal-steel ache. Classic jazz-pop stylist Kat Edmonson contributes “Forever,” a sweet, fanciful throwback worthy of an MGM musical. High, heartrending drama marks “Etoile de la Mer,” by the singer-songwriter Boris Grebenshikov, a.k.a. BG, an icon of Russian rock music and culture and an artist Froom describes as “one of the most fascinating, charismatic people I’ve ever met.” Italy’s Mirco Mariani and Jacqueline Govaert, formerly of the popular Dutch alt-rock band Krezip, bring in two stunningly melodic ballads, “Come Foglie” and “So This Is It,” respectively.

“This music hopefully has some beauty and emotion in a traditional sense, but because of its synthetic nature it becomes more surreal or internal,” Froom says. “It’s almost as if there’s a veil of plastic over it.”

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-11906628-1524501869-1198.jpeg.jpg)