Episode 27. Bob Dylan

The Great Song Adventure is proud to present this archival interview with Bob Dylan, conducted by Paul Zollo in May of 1991 for SongTalk, the journal of the National Academy of Songwriters. It was the first and only interview with Dylan to focus entirely on songwriting. It was the promise of that focus which Dylan appreciated, and one of the main reasons he agreed to do this interview.

Here is Zollo on this conversation with Dylan:

Back in the late ’70s, Dylan complained in an interview about the bizarre range of topics about which interviewers would ask him.

“Well,” said the interviewer, “what do you think they should ask you about?”

“I don’t know,” he answered. “Maybe music?”.

That was always my intention going in, and a sensible one, to talk about songwriting with the man who has profoundly transformed it over the years. And Dylan – like so many other songwriters’ we’ve spoken to -was happy to talk about this ancient art to which he’s devoted his life, and which has been so profoundly shaped by the impact of his own work.

It was a promise I’d always emphasize in my interview requests, that my goal was to have a serious conversation about songwriting, music, songs and the creative process – nothing else. Nothing about the personal life, or anything unrelated to music. Dylan had read some of the past interviews and liked the approach, especially my two-part interview with Paul Simon.

Being a lifelong and devotional songwriter myself, I came informed and inspired to these interviews, which was usually fun and refreshing for those being interviewed, as it’s rare for songwriters to be asked about the mystery and mechanics of music itself, although it is there that their genius lives. And as musicians know – we talk to fellow musicians differently than to civilians. Because music itself is a different language – one which reaches beyond words – and seeing the world through the eyes and heart of a songwriter is a distinct experience, as in being an artist in the music industry.

Unsually I’d let on that I was a songwriter and musician by discussing a song’s key – or chords – which always registers. Because though they rarely discuss it, that is where songwriters live: not only in lyrics and rhymes, but in the many colors of musical keys, major and minor, and those chords used forever to discover and propel melodies. Dylan is a remarkable craftsman – his care for intricate rhyme schemes, perfect meter, singability has been prominent since the start – and he happily answered questions about keys, chords, rhymes and the rest.

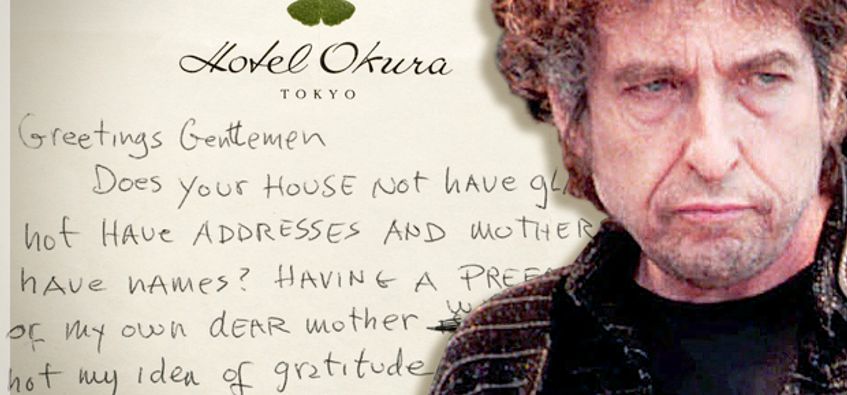

The Dylan SongTalk issue, 1991|

published by the National Academy of Songwriters.

Cover photo by Elliot Landy.

SongTalk was printed on big newspaper pages, like the original Rolling Stone format, and so afforded ample space – more than any conventional magazine – for long in- depth interviews. By being the journal of the National Academy of Songwriters, our focus on the art, craft and history of songwriting was warranted, and my hope that that great songwriters of our time would say yes to us was confirmed through my ten years in this job. Of course, they didn’t all say yes right away. But after dedicated years of polite pestering on my part, most on my big list eventually agreed.

Dylan, of course, was at the toppermost of this list. I hoped he would say yes, of course, but was not even sure our request would even get near him. It did.

This interview – like all the archival ones we are sharing – was done for print – to be read, not to be heard. The audio quality on my little cassette machines wasn’t great but has been improved here digitally, thanks to Ian Sefchick at Capitol Mastering and Elijah Wells.

As Dylan would often pause to reflect on the questions, I could see his mind was stirring and would wait, which is the reason there are several long silences during answers. He was still formulating his response. And anytime Bob Dylan is pausing to reflect and respond, I am in no rush.

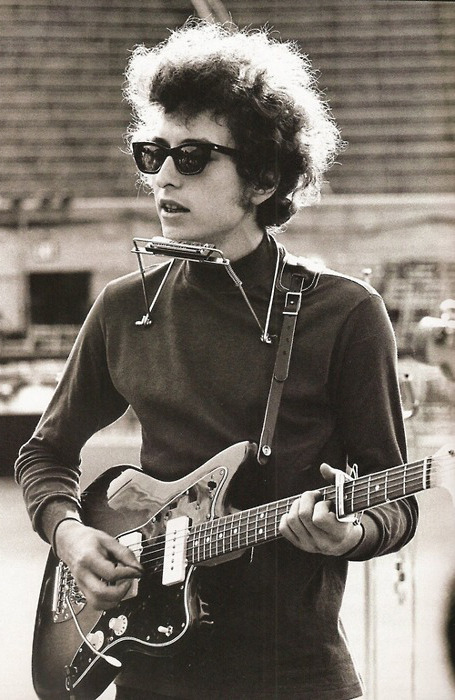

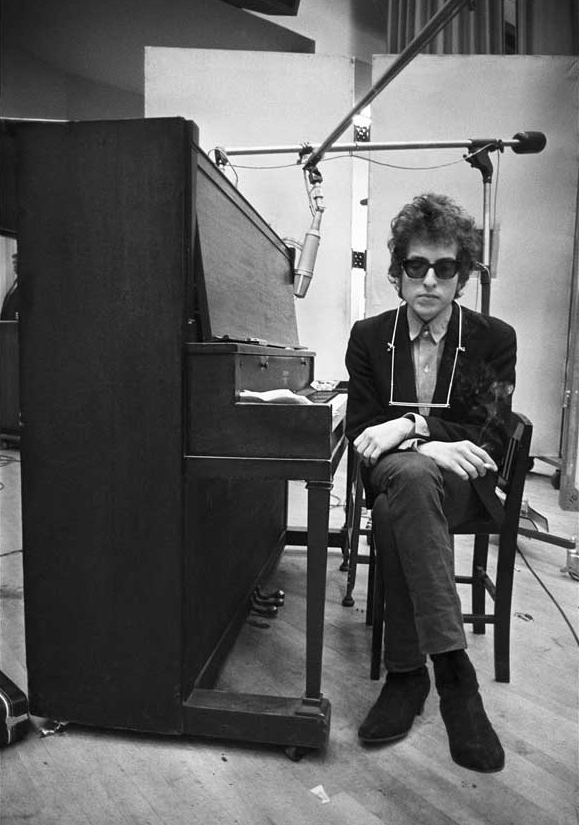

Photo by Elliot Landy.

It was May 8, 1991, and I’d returned to my Hollywood office after lunch to find a pink phone message tacked to the board with an unlikely haiku: “Mr. Dylan appreciates your magazine. He will be in touch.”

At first I suspected it was a joke. I’d been trying to land an interview with Dylan since 1987, when I was appointed editor of SongTalk. But it was no joke; the call came from the office of Elliot Mintz, who was then Dylan’s press rep.

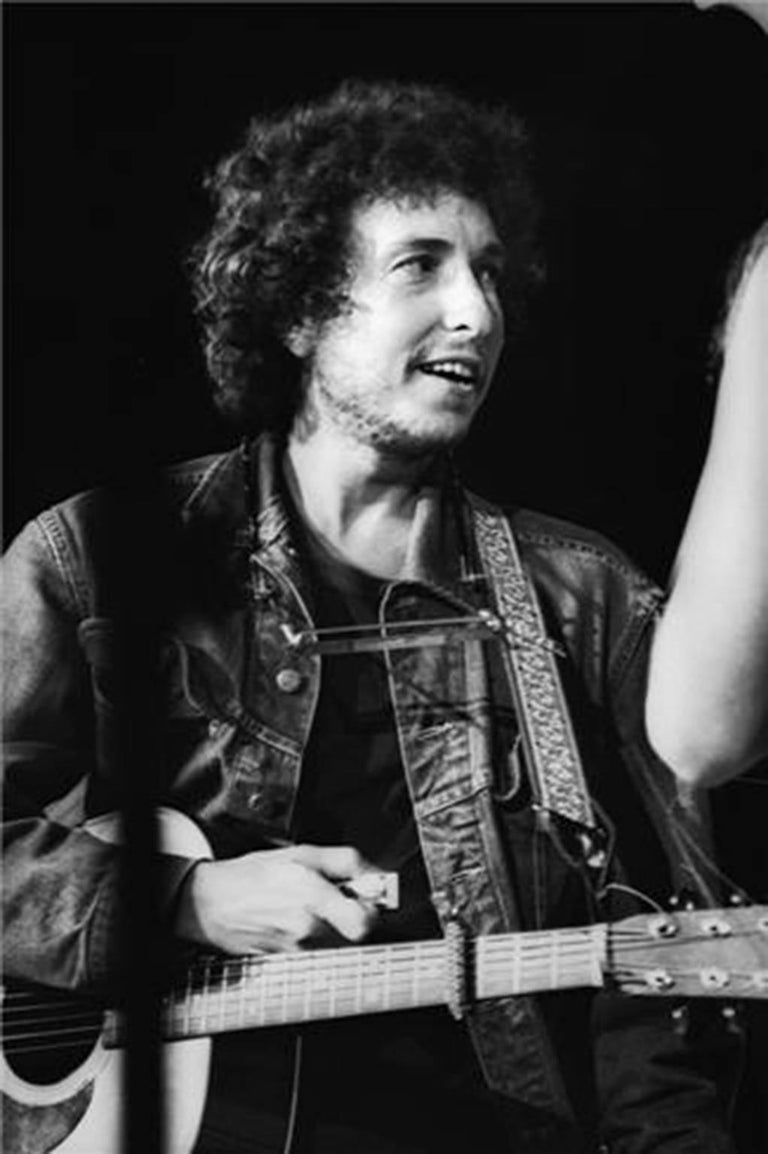

With his son Jesse in Woodstock, 1968. Photo by Elliot Landy.

On the designated day I was summoned to the Beverly Hills Hotel, the big pink lady where stars have stayed and played since the birth of Hollywood. In a bungalow far in the back, Bob Dylan was in a giddy mood. He sang a few lines from the song “People.” Yes, that “People,” the Jule Styne-Bob Merrill standard from Funny Girl made famous by Barbra Streisand. “People who need people,” he sang a capella in that most famous nasality ever, “are the luckiest people in the world …” Then he paused to ask, with much seriousness: “Do you think people who need people are really the luckiest people in the world?”

That he would even know this song, let alone question its premise, says a lot about this man. He thinks deeply about songs, even unlikely ones like this one. Unlike the prevalent perception of him as someone far removed from life as we know it, Dylan pays attention. Searching for some clue as to why he agreed to do this interview with me, he muttered, somewhat in passing, “Man, you and Paul Simon sure talked a lot,” referring to my recent extensive interview with Simon.

The “People” exchange, however, was ultimately omitted from the final interview at the insistence of Mintz, who also demanded the deletion of a few other sections, including one in which Dylan questioned if kids who watched Hendrix burn the flag would do so themselves. Mintz also ended the interview himself by physically turning off both of my tape recorders while Bob was in the middle of discussing his song “Joey,” about the mobster Joey Gallo. I’m still not sure why he was impelled to stop our talk then, but I knew Bob could have kept talking for an hour easy. But it wasn’t to be.

What was to be was Bob having a lot of fun talking about this elusive art form so profoundly impacted by his own hand. His love for songs and songwriters was palpable as was his curiosity. When I told him I loved playing his songs, he asked, “On guitar or on piano?” He wanted to know. Never before or since has he spoken so directly and extensively about songwriting itself, about walking that fine line between unconscious and conscious creation, and ultimately achieving what he defines here himself as “gallantry.”

When you listen to this, keep in mind that Bob was smiling.

“I’ve made shoes for everyone, even you, while I still go barefoot”

From “I and I”

“Songwriting? What do I know about songwriting?” Dylan asked, and then broke into laughter. He was wearing blue jeans and a white tank-top T-shirt, and drinking coffee out of a glass. “It tastes better out of a glass,” he said grinning. His blonde acoustic guitar was leaning on a couch near where we sat. Bob Dylan’s guitar. His influence is so vast that everything that surrounds takes on enlarged significance: Bob Dylan’s moccasins. Bob Dylan’s coat.

And the ghost of ‘lectricity howls in the bones of her face

Where these visions of Johanna have now taken my place.

The harmonicas play the skeleton keys and the rain

And these visions of Johanna are now all that remain

from “Visions of Johanna”

Pete Seeger said, “All songwriters are links in a chain,” yet there are few artists in this evolutionary arc whose influence is as profound as that of Bob Dylan. It’s hard to imagine the art of songwriting as we know it without him. Though he insists in this interview that “somebody else would have done it,” he was the instigator, the one who knew that songs could do more , that they could take on more. He knew that songs could contain a lyrical richness and meaning far beyond the scope of all previous pop songs, and they could possess as much beauty and power as the greatest poetry, and that by being written in rhythm and rhyme and merged with music, they could speak to our souls.

Starting with the models made by his predecessors, such as the talking blues, Dylan quickly discarded old forms and began to fashion new ones. He broke all the rules of songwriting without abandoning the craft and care that holds songs together. He brought the linguistic beauty of Shakespeare, Byron, and Dylan Thomas, and the expansiveness and beat experimentation of Ginsberg, Kerouac and Ferlinghetti, to the folk poetry of Woody Guthrie and Hank Williams. And when the world was still in the midst of accepting this new form, he brought music to a new place again, fusing it with the electricity of rock and roll.

“Basically, he showed that anything goes,” Robbie Robertson said. John Lennon said that it was hearing Dylan that allowed him to make the leap from writing empty pop songs to expressing the actuality of his life and the depths of his own soul. “Help” was a real call for help, he said, and prior to hearing Dylan it didn’t occur to him that songs could contain such direct meaning. When I asked Paul Simon how he made the leap in his writing from fifties rock and roll songs like “Hey Schoolgirl” to writing “Sound Of Silence” he said, “I really can’t imagine it could have been anyone else besides Bob Dylan.”

Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky

With one hand waving free,

Silhouetted by the sea,

Circled by the circus sands,

With all memory and fate

Driven deep beneath the waves

Let me forget about today until tomorrow

ABOVE: Dylan & The Band

BELOW: Dylan & Tom Petty

There’s an unmistakable elegance in Dylan’s words, an almost biblical beauty that he has sustained in his songs throughout the years. He refers to it as “gallantry” in this conversation, and pointed to it as the single quality that sets his songs apart from others. Though he’s maybe more famous for the freedom and expansiveness of his lyrics, all of his songs possess this exquisite care and love for the language. As Shakespeare and Byron did in their times, Dylan has taken English, perhaps the world’s plainest language, and instilled it with a timeless, mythic grace.

Ring them bells, sweet Martha, for the poor man’s son

Ring them bells so the world will know that God is one

Oh, the shepherd is asleep

Where the willows weep

And the mountains are filled with lost sheep

From “Ring Them Bells.”

As much as he has stretched, expanded and redefined the rules of songwriting, Dylan is a tremendously meticulous craftsman. A brutal critic of his own work, he works and reworks the words of his songs in the studio and even continues to rewrite certain ones even after they’ve been recorded and released. “They’re not written in stone,” he said.

With such a wondrous wealth of language at his fingertips, he discards imagery and lines other songwriters would sell their souls to discover. The Bootleg Series, several collections of previously unissued Dylan recordings, offers rare opportunities to view the vast revisions and regrouping his songs go through.

“Idiot Wind” is one of his angriest songs (“You don’t hear a song like that every day,” he said), which he recorded on Blood On The Tracks in a way that reflects this anger, emphasizing lines of condemnation like “one day you’ll be in the ditch, flies buzzin’ around your eyes, blood on your saddle.”

On The Bootleg Series, we get an alternate approach to the song, a quiet, tender reading of the same lines that makes the inherent disquiet of the song even more disturbing, the tenderness of Dylan’s delivery adding a new level of genuine sadness to lines like “people see me all the time and they just can’t remember how to act.”

The peak moment of “Idiot Wind” is the penultimate chorus when Dylan addresses America: ‘Idiot wind, blowing like a circle around my skull, from the Grand Coulee Dam to the Capitol.” On the Bootleg version, this famous line is still in formation: “Idiot wind, blowing every time you move your jaw, from the Grand Coulee Dam to the Mardi Gras.”

“Jokerman,” the opening cut on his great 1983 Infidels album, also went through a similar evolution, as a still unreleased bootleg of the song reveals. Like “Idiot Wind,” the depth and intensity of the lyric is sustained over an extraordinary amount of verses, yet even more scenes were shot that wound up on the cutting room floor, evidence of an artist overflowing with the abundance of creation:

It’s a shadowy world

Skies are slippery gray

A woman just gave birth to a prince today

And dressed him in scarlet

He’ll put the priest in his pocket,

Put the blade to the heat

Take the motherless children off the street

And place them at the feet of a harlot

from “Jokerman” on Infidels

It’s a shadowy world

Skies are slippery gray

A woman just gave birth to a prince today

And she’s dressed in scarlet

He’ll turn priests into pimps

And make all men bark

Take a woman who could have been Joan of Arc

And turn her into a harlot

from “Jokerman” on Outfidels, a bootleg

Often Dylan lays abstraction aside and writes songs as clear and telling as any of Woody Guthrie’s narrative ballads, finding heroes and antiheroes in our modern times as Woody found in his. Some of these subjects might be thought of as questionable choices for heroic treatment, such as underworld boss Joey Gallo, about whom he wrote the astounding song, “Joey.” It’s a song that is remarkable for its cinematic clarity; Dylan paints a picture of a life and death so explicit and exact that we can see every frame of it, and even experience Gallo’s death as if we were sitting there watching it. And he does it with a rhyme scheme and a meter that makes the immediacy of the imagery even more striking:

One day they blew him down

In a clam bar in New York

He could see it coming through the door

As he lifted up his fork.

He pushed the table over to protect his family

Then he staggered out into the streets

Of Little Italy

from “Joey”

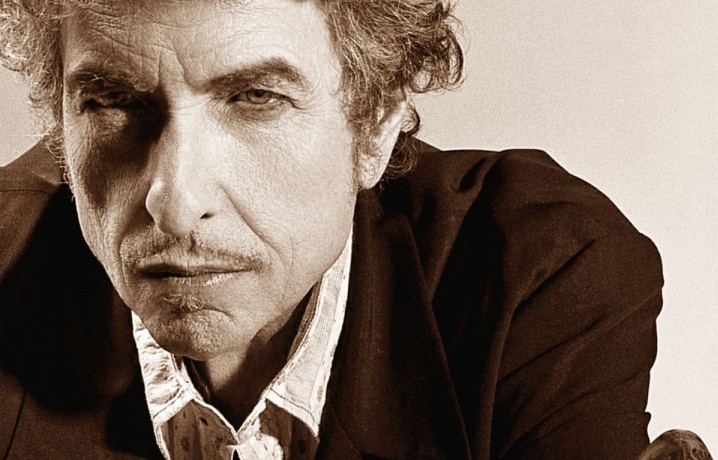

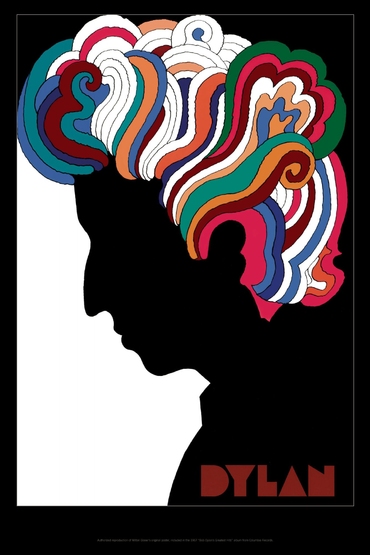

ABOVE: Photo by HENRY DILTZ. BELOW: Milton Glaser’s 1966 poster.

ABOVE: Photo by HENRY DILTZ. BELOW: Milton Glaser’s 1966 poster.

“Yes, well, what can you know about anybody?” Dylan asked, and it’s a good question. He’s been a mystery for years, “kind of impenetrable, really,” Paul Simon said, and that mystery is not penetrated by this interview or any interview. Dylan’s answers are often more enigmatic than the questions themselves, and like his songs, they give you a lot to think about while not necessarily, revealing much about the man.

In person, as others have noted, he is Chaplinesque. He possesses one of the world’s most striking faces; while certain stars might seem surprisingly normal and unimpressive in the flesh, Dylan is perhaps even more startling to confront than one might expect. Seeing those eyes , and that nose , it’s clear it could be no one else than he, and to sit at a table with him and face those iconic features is no less impressive than suddenly finding yourself sitting face to face with William Shakespeare. It’s a face we associate with an enormous, amazing body of work, work that has changed the world. But it’s not really the kind of face one expects to encounter in everyday life.

Though Van Morrison and others have called him the world’s greatest poet, he doesn’t think of himself as a poet. “Poets drown in lakes,” he said to us. Yet he’s written some of the most beautiful poetry the world has known, poetry of love and outrage, of abstraction and clarity, of timelessness and relativity. Though he is faced with the evidence of a catalogue of songs that would contain the whole careers of a dozen fine songwriters, Dylan told us he doesn’t consider himself to be a professional songwriter.

“For me it’s always been more confessional than professional,” he said in distinctive Dylan cadence. “My songs aren’t written on a schedule.”

Well, how are they written, I asked? This is the question at the heart of this interview, the main one that comes to mind when looking over all the albums, or witnessing the amazing array of moods, masks, styles and forms. How has he done it? It was the first question asked, and though he deflected it at first with his customary humor, it’s a question we returned to a few times.

“Start me off somewhere,” he said smiling, as if he might be left alone to divulge the secrets of his songwriting, and our talk began.