Episode 6. Leonard Cohen, A 1992 Archival Interview

The Great Song Adventure is honored to bring you this archival interview with Leonard Cohen, conducted by Paul Zollo in 1992 at Leonard’s Los Angeles home. Of all the interviews Zollo has conducted over these past three decades, with the exception of his Bob Dylan interview, none has been quoted so thoroughly over the years as this one. What follows is Zollo’s account of that interview, and reflections on the life and work of Leonard Cohen, who, after completing his final album, You Want It Darker, died on November 7, 2016. He was 82.

“If I knew where the good songs came from, I would go there more often.”

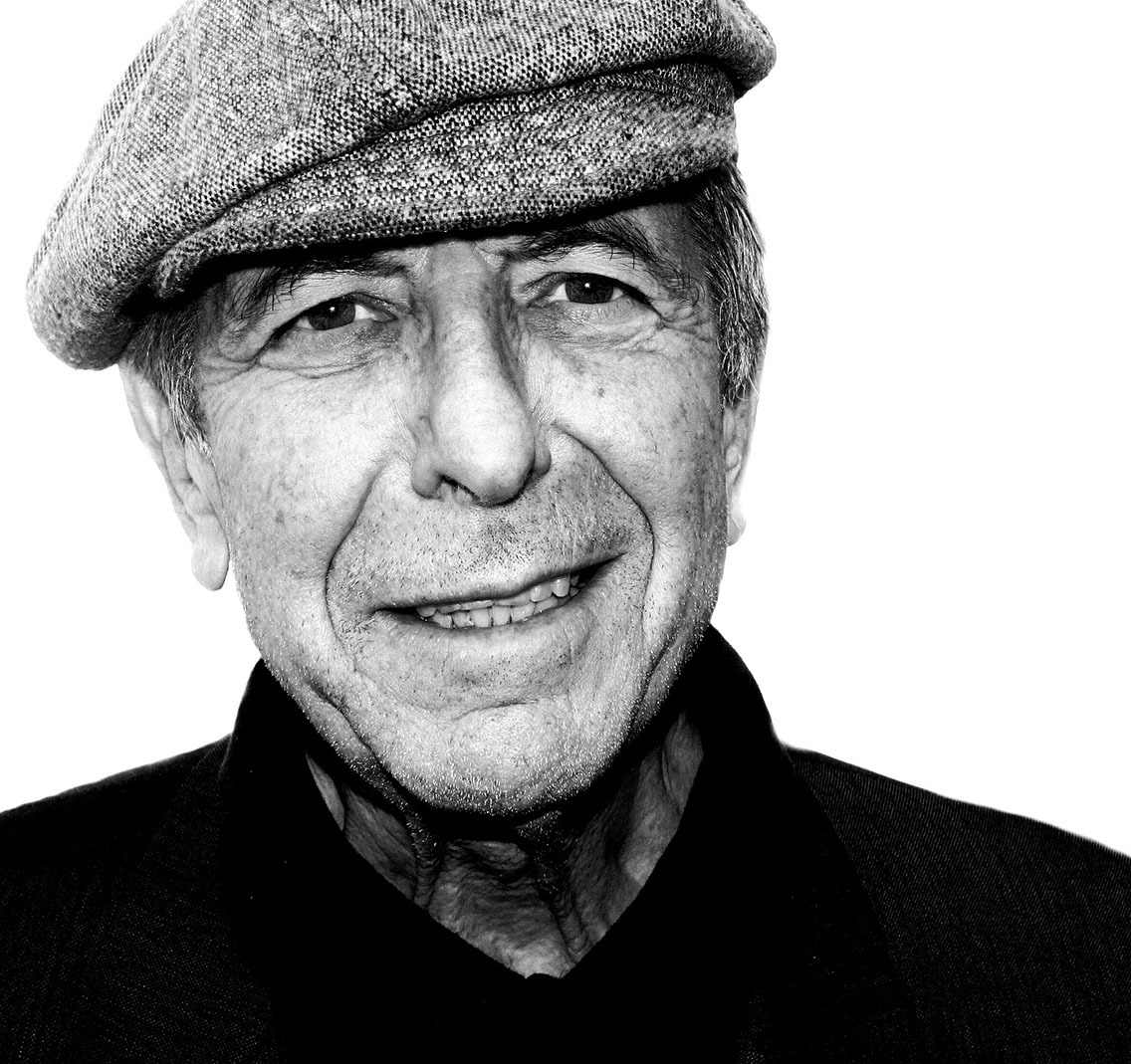

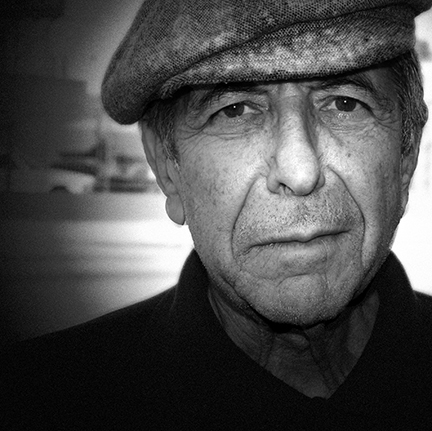

Leonard Cohen on Pico, 1994.

Photo by Paul Zollo.

I remember it like it was yesterday, back when I was ten years old and learning how to play guitar. In front of me were the lyrics and chords for Leonard’s song “Suzanne.”

I remember thinking, “How does someone write something this beautiful?” It seemed like a miracle to me then. And it still does.

So when receiving the great privilege of sitting down with him myself to talk about songwriting, that is where I began. With the admission that for most of my life, I have been pondering the mystery of “Suzanne,” which resounded then, and still does, as a miracle. How exactly does one write a song like that?

He smiled that warm, beatific Leonard smile when I said this, and did not demur.

“It is a miracle,” he answered. “If I knew where the good songs came from, I would go there more often.”

And in that one answer came the crystallization of this man’s greatness. With just a few words, all of Leonard is there: his humility, humor, reverence, mystery, truth and dedication. Dedication to the mystery itself, to the realm into which all songwriters reach to find their songs.

Unlike most humans who rarely finish entire sentences, he spoke in what felt more like parables than paragraphs, with an eloquence both ancient and modern, serious and comic, conversational and poetic. His ideas were informed by religious wisdom, from Judaism, as well as other religions, and the ancient elegance of Biblical verse. Never was this more evident than when asked about the current quality of popular song, and the widespread conviction of many that meaningful songs are no longer written. His answer is not only stunning for the beauty of its Whitmanesque language, but also for a perspective that is greater than the usual, and more generous in its understanding of how songs figure into people’s lives: .

“There are always meaningful songs for somebody,” he said. “People are doing their courting, people are finding their wives, people are making babies, people are washing their dishes, people are getting through the day, with songs that we may find insignificant. But their significance is affirmed by others. There’s always someone affirming the significance of a song by taking a woman into his arms or by getting through the night. That’s what dignifies the song. Songs don’t dignify human activity. Human activity dignifies the song.”

In 1994, I interviewed Anjani, the singer-musician who loved and lived with Leonard for years and did a whole album of his words with her music. We met at a café in mid-L.A. and the great man himself, Leonard, accompanied her. Of course, being him he knew right away I would be unable to conduct a meaningful interview with him sitting there. So he immediately assured us that he would sit elsewhere while we spoke.

We did the interview, and afterwards I made an admission to Anjani. Which was that it was hard to fathom actually living a regular life with Leonard Cohen. I did know he was a man, after all. But to songwriters, I said, he is a god.

She laughed heartily when I said that, and answered, “Oh trust me, he’s a man! He is definitely a man!”

Now with his mortal life complete, it seems she must have been right. But there are very few men who have ever done what he did. Even when the industry as he knew it essentially collapsed, never did he waver from the thing that mattered most: the work. If it took him seven years to perfect a song, even to the extent of writing forty or more verses, he would take seven years. There was no rush. Nothing mattered more. When he would be up at Mt. Baldy, serving time as a Buddhist monk, he would be working on songs in his head. During his last year, when he was in severe pain and immobilized, he worked on songs. The work never stopped.

“My ordinary state of mind is very much like the waiting room at the DMV… So to penetrate this chattering and this meaningless debate that is occupying most of my attention, I have to come up with something that really speaks to my deepest interest. Otherwise I just nod off in one way or another. So to find that song, that urgent song, takes a lot of versions and a lot of work and a lot of sweat.”

– Leonard Cohen

Songwriting was for him was, as other miracle songs such as “Hallelujah” affirm, more than a job. It was a calling. His highest calling. And he built a beautiful and indestructible tower of song, brick by brick, day by day, year by year. Like all of his songs, it has been built to last.

“It begins with an appetite,” he said, describing the way he started a song, “to discover my self-respect. To redeem the day. So the day does not go down in debt.”

Leonard Cohen & Paul Zollo at the Top of the Tower of Song, 1992.

Photo by Henry Diltz.

“Freedom and restriction are just luxurious terms to one who is locked in a dungeon in the tower of song.” — Leonard Cohen

That day we met remains etched in shining memory forever. Even the recognition that Leonard lived in the same world in which we all lived, and even in the same city, was a revelation. His songs always suggested he existed in a whole other realm, separate from mundane human existence.

He answered the door like an old friend, and with great warmth, gratitude and abundant humor, he made me feel instantly at ease. His passion for songs – and for the process of writing them – was palpable and infectious. Not only did he delight in explaining how endless were his revisions, he proudly led me upstairs to where his journals were kept, and read me many of the great verses he discarded.

This was 1992, almost ten years since his own recording of “Hallelujah” was released, yet still before it became the beloved standard it’s become, recorded by almost 300 different artists and in many languages. John Cale’s version came out in 1991, but it was not until the season of Jeff Buckley’s rendition in 2007, and subsequent recordings by kd lang, Rufus Wainwright and others, that the song became world famous. This transformed and enervated Leonard’s career in a profound way, leading to several triumphant and glorious world tours.

Yet back in 1992, at the time of this talk, that shift had yet to commence. Few people yet knew or loved “Hallelujah,” and Leonard’s albums, though always brilliant, made little impact, especially in America. Even music videos he’d make, which were shown in other countries, rarely were seen at all in this country.

We met just after he’d finished a masterpiece, his album The Future, which reflected the turmoil of America and the world in modern times. It’s an album of remarkably epic and expansive ferocity, including astounding songs such as “The Future” and “Democracy.” In this interview, he discusses the origins of both, and shares verses that he discarded from them. Also, being Leonard, even his answer about why those verses were discarded is pure poetry, and beautiful.

More than anything, it’s his unflagging devotional diligence, and genuine love of work, which made the biggest impact on so many. His resolute determination never to settle, to never allow a lesser line to live if a better one can be found, was a great and ongoing education for so many. Songwriting, as he explained, did not come easy. It was work, and he felt artists were wrong to ever consider anything wrong with work.

“But why shouldn’t my work be hard?” he asked. “One is distracted by this notion that there is such a thing as inspiration, that it comes fast and easy. Some people are graced by that style. I’m not. So I have to work hard as any stiff, to come up with the payload.”

In what remains one of the my favorite part of the interview, both delightfully funny and poetic, is his answer to my question of what his work entails.

“Anything,” he said, “ that I can bring to it: Thought, meditation, drinking, disillusion, insomnia, vacations. Because once the song enters the mill, it’s worked on by everything that I can summon. And I need everything. I try everything. I try to ignore it, try to repress it, try to get high, try to get intoxicated, try to get sober, all the versions of myself that I can summon are summoned to participate in this project, this work force. I try everything. I’ll do anything. By any means possible.”

So, I asked, do any of these things work better than others?

“No,” he said with a smile. “Nothing works. Nothing works.”

Yet, even with this admission, he created remarkable songs over the decades, songs which shone in a much richer, more epic way than those written by most of his peers, with the exception of a few. Bob Dylan, though the recipient of much more worldwide reverence for his work than Leonard, greatly admired Leonard’s songs. Leonard also greatly admired Dylan, though it seems likely Leonard would have still been Leonard no matter what, unlike most contemporary songwriters. As the poet Allen Ginsberg, a friend to both, said, “Dylan blew everybody’s mind when he emerged. Everyone except Leonard Cohen, that is.”

During Leonard’s lifetime, Dylan was his stalwart champion, reminding a world that seemed not to care at times that what Leonard was doing was unlike anything else. Following the release of Leonard’s Various Positions in 1984, which contained “Hallelujah” yet was ignored by the mass of record buyers, Dylan alerted the world to what they were missing. “These are more than songs,” Dylan said.” These are prayers.” Those words, reflecting the holy if broken hallelujah which echoes through Leonard’s entire songbook, brought multitudes to Leonard’s music.

Leonard,1994. Photo by Paul Zollo.

Following Leonard’s death, Dylan extolled Leonard’s greatness. As someone who understands better than most humans what a song is, as opposed to a poem, he pushed back against the prevalent pattern of memorializing Leonard as a poet, and not a songwriter. Leonard did write books of poems, as well as two novels. But his life was dedicated, with vast devotional intensity, to being a songwriter.

Yet because of Leonard’s prodigiously ingenious way with words, like Dylan, he’s often celebrated not as songwriters, but as poets. As if being a poet in modern times is a higher calling in some way. Yet as we know, in these times, it’s the songwriters who have had the greatest impact on our culture, much more so than poets. Dylan identifies Leonard’s genius as a songwriter, combining both words and music.

“When people talk about Leonard,” Dylan said, “they fail to mention his melodies, which to me, along with his lyrics, are his greatest genius. Even the counterpoint lines—they give a celestial character and melodic lift to every one of his songs. As far as I know, no one else comes close to this in modern music. His gift or genius is in his connection to the music of the spheres.”

Leonard also felt great and oft-expressed admiration for Dylan. In this interview he compared Dylan’s lyrics to the “unhewn stone” on which ancient Jews erected their altar, as opposed to slick, smooth stone.

“Dylan has a lot of lines that have the feel of unhewn stone,” Leonard said. “It’s inspired but not polished. That is not to say he doesn’t have lyrics of great polish. That kind of genius can manifest all the forms and all the styles.”

During the last year of his life, near death, in pain so great, said his son Adam, that he had to turn to forces much stronger than medicine, Leonard finished his final album, You Want It Darker. Too weak to do a series of promotional interviews to launch the album, Leonard did one press event at the beautiful Canadian consulate mansion in Los Angeles.

Only invited guests were present, including friends and collaborators and Leonard’s son, Adam, who produced the album. Also invited was a cadre of mostly foreign journalists and a few lucky Americans (including me), all of whom had expressed great love and reverence for Leonard in their work over the years. It was October 13, 2016, the same day the announcement was made that Dylan had been awarded with the Nobel Prize for Literature. It was the first time a songwriter had ever earned this distinction. Many there suggested Leonard should have been the first to get it.

Be Thy Holy Name

Vilified and crucified

In the human frame

A million candles burning

For the help that never came

You want it darker

We kill the flame

Hineni Hineni

I’m ready, my Lord.”

From “You Want It Darker”

By Leonard Cohen

From the title song of his final album, it ends with the ancient Hebrew prayer. Hineni means “I’m here,” and is followed in English, with “I’m ready, my Lord.”

Knowing of his grave illness, and a foreboding recent statement he made suggesting he was ready to be done with this life, the press asked about this song, which seemed to be expressing an acceptance of imminent death. His answer was startling, both in its eloquence as well as its unflinching embrace of the inevitable, and its effect on him:

“I don’t really know the genesis, the origin, enabling that declaration of readiness,” he said, “no matter what the outcome. That is a part of everyone’s soul. We all are motivated by deep impulses and deep appetites to serve, even though we may not be able to locate that which are willing to serve. So this is just a part of my nature. And I think it would also be my nature to offer one’s self when the emergency becomes articulate. It’s only when the emergency becomes articulate that we can locate that willingness to serve.”

A kind of stunned silence followed, as the crowd absorbed the fullness of what he said. Sensing this, he added, “That’s getting too heavy. I’m sorry. Strike that.”

Much laughter. Even weakened, his voice softer than ever, the man knew how to work a crowd.

When asked his opinion about the news that Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize, Leonard, with hardly a second’s hesitation, said, “To me, giving that award to Dylan is like pinning a medal on Mt. Everest for being the highest mountain.” Though many laughed at this precise and generous metaphor, most of the foreign press was completely baffled by it, as it simply did not translate. Afterwards they crowded around, asking for an explanation. I did my best to explain, but not sure I succeeded.

At the conclusion of our last night with him, he left us all with hope that we would see and hear from him again. “Thanks for coming, friends,” he said warmly. “I really appreciate it. I really appreciated your standing up when I came into the room. Hoping to do this again. I intend to stick around till 120.”

He also admitted to a fondness for hummingbirds. “I have always loved those magical little creatures,” he said, and recited a recently composed song about them, only words so far, no music.

Listen to the hummingbird

Whose wings you cannot see

Listen to the hummingbird

Don’t listen to me

Listen to the butterfly

Whose days but number three

Listen to the butterfly

Don’t listen to me

Listen to the mind of God

Which doesn’t need to be

Listen to the mind of God

Don’t listen to me

After the applause faded, he added, “I would say the hummingbird deserves royalties on that one.” When he was asked if it would be on the next album, he said, softly, “God willing.”

That a songwriter and singer would end a long and remarkable career with the statement, “Don’t listen to me,” says everything about the soul of Leonard Cohen. At the end he pointed us all away from this light shining on him to the light inside all things, the source of all songs. The place where the great songs came from.

It’s where he is now.

Hallelujah.