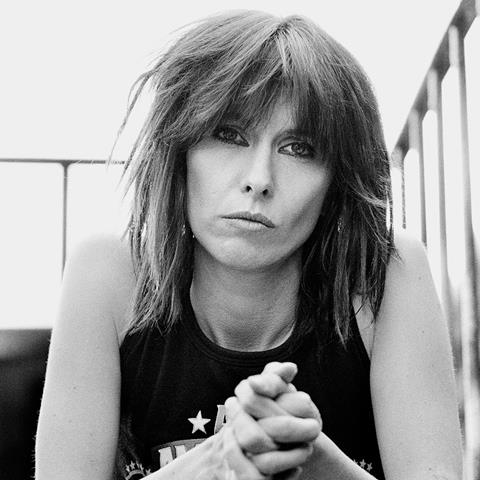

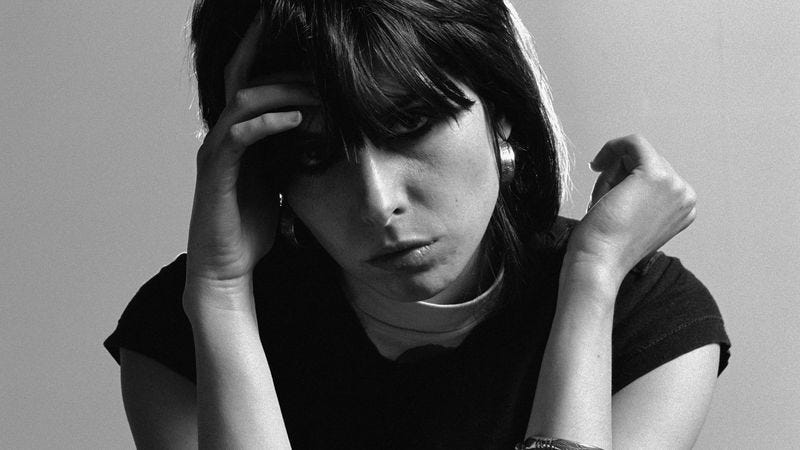

Episode 12. Chrissie Hynde

From the archives, recorded in 2009.

Now the reason we’re here

As man and woman

Is to love each other

Take care of each other

When love walks in the room

Everybody stand up

Oh it’s good, good, good

Like Brigitte Bardot

From “Message of Love”

“I just didn’t want to be a waitress,” she said in answer to why she chose this path. It’s a path she followed from the concrete climes of Akron to England, where she started The Pretenders. Asked if her music would have been vastly different had she never left America, she said, “Yeah, because I would have killed myself.”

Some songwriters are happy to talk about the greatness of their great songs, and how they wrote them. Others openly ackowledge the greatness, but ascribe its birth to a source beyond them. Many don’t doubt the spiritual aspects of songwriting, and for that reason are careful not to examine it too closely, so as not to scare it away.

But with very rare exceptions, none have denied they are songwriters. Chrissie’s that rare exception. Many times during our talk, which took place in 2009, she suggested she’s not even a real songwriter.

And I understood why. This is Chrissie Hynde, after all, who has always defied easy definitions.

Not only is she no diva, she’s an anti-diva. Because, like Mose Allison (whose name comes up in regard to her assertion that much of British rock was stolen from him), she’s simply one of the coolest people around. Like him, she’s written many masterpieces over the years. Yet will be the last to sing their own praises. Let people make up their own mind.

In fact, she’s so extremely reticent to affect any pretension, any sort of “and then I wrote” songwriterly pride, that she repeatedly dismissed praise through our conversation to exclaim, “This sounds so lame…”

And when our conversation was interrupted the second time by someone at her door, she came back and said, “You’re gonna think I have a life. I don’t.”

And when pressed to divulge the secrets of her process, she said this: “It depends on how much pot I’ve been smoking, how many bottles of wine I’ve drunk. It’s usually just in a puddle on the floor in the morning, and is a waste of time. But once in a while, it works.”

“Jesus Christ came down here as a living man

If he can live a life of virtue then I hope I can

Do unto others as you would have a turn

Come back here and repeat until you learn, learn, learn…”

From “Boots of Chinese Plastic”

She is, of course, the writer of not one but several songs that have become rock standards, beloved and undisputed rock hits. Yet this steadfast refusal to take herself too seriously as a songwriter spoke to a fear that any light shone too directly into that realm from which songs emerge might destroy it. She did, however, have nothing but pure praise for her fellow Pretenders, past and present, especially James Honeyman-Scott, who died for a heroin overdose in 1982.

The only real test of a song is that of time. Her songs have passed that test. Though she emerged in an era of booming drum machines and synth pads, she steered the Pretenders always with a purist’s respect for the traditions of rock & roll. She wasn’t here to rewrite the rules. She was here to write great songs, songs a great singer can sink her teeth into, songs that have lasted far beyond the era in which they were written. Whether she wants to admit it, she’s not only a great songwriter, she’s a hit songwriter. But every now and then, due to polite persistence, she gave in, and talked about how she’s done it. She even indulged my desire to name many of her songs for her immediate response, demurring at first before saying, “Okay, whatever. Go ahead and do your thing.”

So I did. And she gave a wonderfully expansive answer to “Brass in Pocket” that was beyond expectations, proving so poignantly how deep these songs do go, in her psyche and her history. Though I know she’d never admit it, it became evident these songs felt like her children, and so taking credit for them songs was like a parent taking credit for the success of a child. It’s the kid who is great, not the mom.

She was born in Akron, Ohio in September of 1951. Her dad worked for the Yellow Pages. She wrote her first song at the age of 14 after learning two guitar chords, recognizing even then that limitations create possibility. “You only need one chord to write a song,” she explains. “Look at all those James Brown songs.”

She hated high school and all it entailed, partly because her eyes were already set firmly on a musical future: “I never went to a dance, I never went out on a date, I never went steady,” she remembered. “It became pretty awful for me. Except, of course, I could go see bands, and that was the kick. I used to go to Cleveland just to see any band. So I was in love a lot of the time, but mostly with guys in bands that I had never met. For me, knowing that Brian Jones was out there, and later Iggy Pop, made it kind of hard for me to get too interested in the guys that were around me. I had… bigger things in mind.”

She went to Kent State to study art, and was there during the tragic shooting of students by the Ohio National Guard. Jeffrey Miller, who was shot and killed that day, was one of her friends. She wanted out of Ohio, out of America. Discovering the Brit music mag NME, she saved enough money to move to London. She landed a writing gig with NME but it didn’t last long – her next job was in Malcolm MacLaren’s SEX shop. It’s there she met Syd Vicious, and tried – according to legend – to persuade him into marriage, so she could become a British citizen. He passed.

She joined a series of bands – first as singer in The Frenchies, then guitarist in Masters of the Backside, and the Johnny Moped band. Mick Jones invited her to join a nascent pre-Joe Strummer incarnation of what would be the Clash, and they went on a British tour together, but Chrissie wasn’t happy. She wanted her own band. But it would take time.

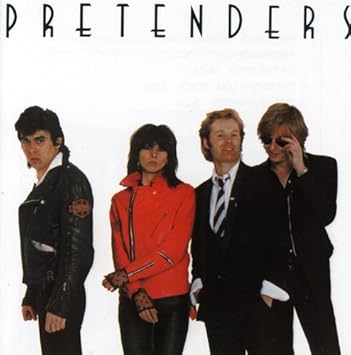

Her visa ran out and she had to go back to Ohio, but returned as soon as possible. In 1978 she succeeded at last in realizing her dream, and formed The Pretenders in Hereford with three Brits: James Honeyman-Scott on lead guitar and keyboards, Pete Farndon on bass and Martin Chambers on drums. Everyone in the band sang. Their first single was the Nick Lowe-produced “Stop Your Sobbing,” a Kinks song. In 1980 came the eponymous debut album, a critical and commercial success both in the US and the UK – which led to a great succession of amazing songs penned by Chrissie: “Brass In Pocket,” “Kid,” “Back On The Chain Gang,” “Middle of the Road,” “Message of Love” and so many more.

But tragedy hit the band fast and early – first Honeyman-Scott’s death, then Farndon’s subsequent bathtub drowning, after having being fired from the band for being too messed up on drugs. Here was one of the greatest new bands on the scene, launching the ’80s with the promise of great rock to come, and suddenly half of the group was gone.

But she never was derailed for long. She also never had any desire to establish a solo career – and chose instead to reinvent the Pretenders many times over the years – even replacing Chambers, but later bringing him back as on the recent tour. “I know that the Pretenders have looked like a tribute band for the last 20 years,” she said at their Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction, “and we’re paying tribute to James Honeyman Scott and Pete Farndon, without whom we wouldn’t be here. And on the other hand, without us, they might have been here, but that’s the way it works in rock & roll.”

A circumstance beyond our control

The phone, the TV and the news of the world

Got in the house like a pigeon from hell

Threw sand in our eyes and descended like flies

Put us back on the train

Back on the chain gang

From “Back On The Chain Gang”

By Chrissie Hynde

The ostensible purpose of this interview was to discuss The Pretenders Live In London, a DVD of a passionately joyful live show with the current line-up: Martin Chambers on drums, James Walbourne on guitar, Nick Wilkinson on bass and Eric Heywood on pedal steel. Her punk ethic still comes across when talking about it – as opposed to her peers that involve themselves in all angles of marketing and commercial calculations, she had no inclination to even view the DVD, and tried to beg out of it. But when she finally did view it, she was surprised by how great it was. And she was happy.

“You have to keep digging deeper over the years,” she said in regard to parenthood’s tendency to soften the edges of a rocker. Yet she remains one of rock’s most fiercely gifted songwriters, and, as evidenced by the great songs she wrote for Break Up The Concrete, she’s still very much at the top of her game. Of course she won’t cop to it. And adds that she still feels like a sham – a pretender, if you will – who someday might be found out. “Compared to Dylan and Neil Young,” she says, “I’m still in the minor leagues.”

Yet few songwriters have talked about the sad suburbanization of America with more poignancy than this ex-patriate, who often returned to Ohio – even opening a Vegan restaurant there – and yet found her homecomings laced always with increasing sorrow at the sight of her hometown’s decimation. It’s a subject that has recurred many times in her work, most notably in “My City Was Gone” but also in more recent songs like “Break Up The Concrete,” a great example of outrage being projected, not unlike Neil Young’s “Ohio” about the Kent State massacre, with the assist of a great rock groove.

And when you hear “Boots of Chinese Plastic” from Concrete, with its distinctive blend of Buddhism, bravado and a taut Buddy Holly beat, you hear a songwriter engaged, as inspired as when The Pretenders first emerged.

Illusion fills my head like an empty can

I spent a million lifetimes lovin the same man

Every drug that runs though the vein

Always makes its way back to the heart again

And by the way you look fantastic

In your boots of Chinese plastic

From “Boots of Chinese Plastic”

By Chrissie Hynde