Episode 1. Van Dyke Parks

“A song,” he once said, “should not fall apart on the street like a cheap watch.” This devotion to the durability of the song, and reverence for songwriting is one of many reasons Van Dyke Parks is a hero to so many.

When Louise and Paul first discussed doing this podcast, the same name kept coming up. Van Dyke Parks. Not only is he a legendary songwriter-composer-arranger-producer, he’s famously eloquent, funny and brilliant on pretty much any subject, and especially on music and its mysteries.

He’s also someone they’ve both known personally for years. Paul first interviewed him in 1988 for SongTalk magazine (included in Songwriters On Songwriting) just after the release of Van Dyke’s album Tokyo Rose. He’s also interviewed him several times since then, including once for the documentary Legends of the Canyon.

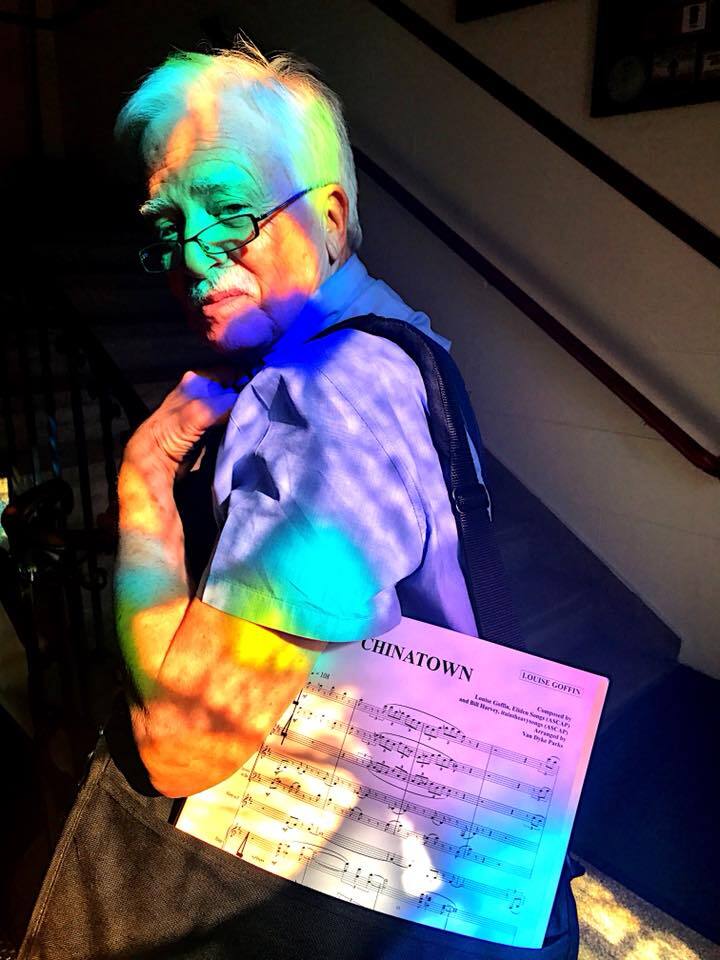

Louise has worked with him on several occasions, and most recently on “Chinatown,” a song from her new album All These Hellos for which Van Dyke wrote a glorious orchestral arrangement evoking old Hollywood. We get to hear a portion of that record, which is a duet with Rufus Wainright.

Songwriting, he said, is a “triumph of the human spirit.” It’s a feeling all songwriters know, yet few have crystalized so ideally. He’s been a luminous wordsmith since the start of his legendary career, starting with the brilliant Song Cycle in 1968 and also with the lyrics to songs such as “Surf’s Up” and “Heroes and Villains” which he wrote with another genius, Brian Wilson, for The Beach Boys.

He’s also an astounding composer, one of the greatest melodists of our time. After Song Cycle came an unbroken chain of masterpieces, each with resplendent melodics and orchestral settings that spring not from rock and roll, but 19th and early 20th century inspirations much more about pure melody and beautifully rendered linguistics than rock and roll. In 1985 came the delightful Americana of Jump (1985), a heartwarming song cycle based on the tales of Brer Rabbit. While others were alienating us with bombast and distortion, he brought us charm and beauty.

Then Tokyo Rose (1989), a brilliant orchestral scrutiny of America’s evolving relationship with Japan. Next the timeless magic of Orange Crate Art, a resplendently sumptuous series of songs written for Brian Wilson to sing, delving into the California endless summer spirit born long before any of us were born. Then came Songs Cycled, consisting of the many brilliant singles he released during previous years, with songs reflecting modern times more than ever, such as “Black Gold,” about oil treasures and spillage both, and “Wall Street,” about American greed, 9-11 and more. In a time when most songs contain little content, his remind us of what songs can do, expressing content previously untouched in song, yet so vividly vital, and always contained within music of great richness.

Born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi in 1943 and raised in Lake Charles, Louisiana, he was a child star who appeared on “The Honeymooners” and other TV shows, sang at the Met, and studied music at Carnegie Tech before coming to Los Angeles and becoming the beloved Van Dyke Parks. In addition to the great albums of his own, he contributed to countless others, including those by Ry Cooder, Little Feat, Lowell George, Inara George, Harry Nilsson, Randy Newman, Ringo Starr, U2 and many others. For a short time he was even a member of Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention, in which Frank called him Pinocchio. He’s scored many movies, including Robert Altman’s Popeye and The Two Jakes, the sequel to Chinatown directed by Jack Nicholson.

Unlike many musicians and songwriters who can’t, or don’t want to, answer hard questions about music, Van Dyke is not only willing but brilliant in his ability to verbalize even those things beyond words. Asked what makes a melody powerful, for example, Dave Brubeck said, “The secret of a melody is a secret.”

Whereas Van Dyke said this:

“A melody is at first an exposition. It goes somewhere from somewhere. A melody takes us through time. [It] indicates its harmonic development… a good melody can be evocative. It can remind you of some place that you’ve been. And if a melody jars a memory, it serves a great purpose.”

Song Cycle, to this day, is famous for its abstract, stream-of-consciousness verbiage. But from that style he soon moved on to songs of clear content, and narrative grace. “I retired from that,” he explained, “but I still think it’s a valid idiom… I still have this iconoclastic, highly individual approach to songwriting. And I enjoy it very much. It’s an honor.”

Always brilliant with the use of physical symbols, he provided one of the best for the often rudderless navigation which songwriting demands. It came from his work scoring Popeye with Robert Altman, who was shooting an object on a boat from a boat. “There were no fixed points, you see. I feel very much like I am at sea” when writing songs.

“Songwriting is a matter of self-discovery,” he explained. “I don’t think a song should fall apart like a cheap watch on the street… it’s important to make a song a renewable resource. Something that can be listened to again.”

Timeless song has fortified his spirit: “Songs have a tremendous closeness to the soul. The psalms was my first all-time favorite in the Bible. I’ve always venerated a timeless, higher power.”

But how does one maintain a good attitude when the song isn’t coming? “I don’t get my knickers twisted,” he answered. “Composure is what it’s all about. But you must go there. You must make a habit of the luxury and the sanctuary that songwriting provides. You’re creating a world that you’re subject to… It’s transcendental, beyond possession. It really is.”

On the subject of these kinds of interviews with songwriters about songwriting, he said, “Everything is revealed, yet nothing is revealed. What is transferable is this sense of courage, of derring-do… This is infectious. And confirmational. It’s as helpful as belonging to some religious sect, to me. Hearing someone say, ‘Amen.’”

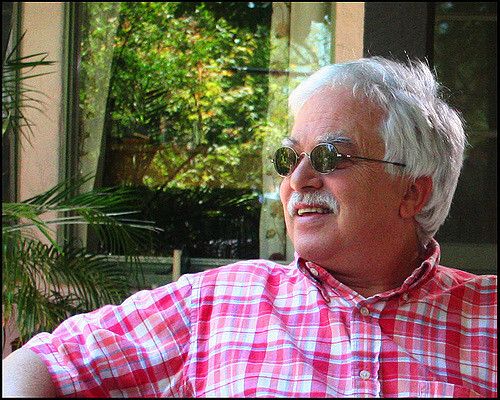

Our interview with him was conducted at his Hollywood home, where his wife Sally brought iced tea and took photos, and we watched as young lovers courted and kissed right outside his front window.

“A song,” he once said, “should not fall apart on the street like a cheap watch.” This devotion to the durability of the song, and reverence for songwriting is one of many reasons Van Dyke Parks is a hero to so many.

When Louise and Paul first discussed doing this podcast, the same name kept coming up. Van Dyke Parks. Not only is he a legendary songwriter-composer-arranger-producer, he’s famously eloquent, funny and brilliant on pretty much any subject, and especially on music and its mysteries.

He’s also someone they’ve both known personally for years. Paul first interviewed him in 1988 for SongTalk magazine (included in Songwriters On Songwriting) just after the release of Van Dyke’s album Tokyo Rose. He’s also interviewed him several times since then, including once for the documentary Legends of the Canyon.

Louise has worked with him on several occasions, and most recently on “Chinatown,” a song from her new album All These Hellos for which Van Dyke wrote a glorious orchestral arrangement evoking old Hollywood. We get to hear a portion of that record, which is a duet with Rufus Wainright.

Songwriting, he said, is a “triumph of the human spirit.” It’s a feeling all songwriters know, yet few have crystalized so ideally. He’s been a luminous wordsmith since the start of his legendary career, starting with the brilliant Song Cycle in 1968 and also with the lyrics to songs such as “Surf’s Up” and “Heroes and Villains” which he wrote with another genius, Brian Wilson, for The Beach Boys.

He’s also an astounding composer, one of the greatest melodists of our time. After Song Cycle came an unbroken chain of masterpieces, each with resplendent melodics and orchestral settings that spring not from rock and roll, but 19th and early 20th century inspirations much more about pure melody and beautifully rendered linguistics than rock and roll. In 1985 came the delightful Americana of Jump (1985), a heartwarming song cycle based on the tales of Brer Rabbit. While others were alienating us with bombast and distortion, he brought us charm and beauty.

Then Tokyo Rose (1989), a brilliant orchestral scrutiny of America’s evolving relationship with Japan. Next the timeless magic of Orange Crate Art, a resplendently sumptuous series of songs written for Brian Wilson to sing, delving into the California endless summer spirit born long before any of us were born. Then came Songs Cycled, consisting of the many brilliant singles he released during previous years, with songs reflecting modern times more than ever, such as “Black Gold,” about oil treasures and spillage both, and “Wall Street,” about American greed, 9-11 and more. In a time when most songs contain little content, his remind us of what songs can do, expressing content previously untouched in song, yet so vividly vital, and always contained within music of great richness.

Born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi in 1943 and raised in Lake Charles, Louisiana, he was a child star who appeared on “The Honeymooners” and other TV shows, sang at the Met, and studied music at Carnegie Tech before coming to Los Angeles and becoming the beloved Van Dyke Parks. In addition to the great albums of his own, he contributed to countless others, including those by Ry Cooder, Little Feat, Lowell George, Inara George, Harry Nilsson, Randy Newman, Ringo Starr, U2 and many others. For a short time he was even a member of Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention, in which Frank called him Pinocchio. He’s scored many movies, including Robert Altman’s Popeye and The Two Jakes, the sequel to Chinatown directed by Jack Nicholson.

Unlike many musicians and songwriters who can’t, or don’t want to, answer hard questions about music, Van Dyke is not only willing but brilliant in his ability to verbalize even those things beyond words. Asked what makes a melody powerful, for example, Dave Brubeck said, “The secret of a melody is a secret.”

Whereas Van Dyke said this:

“A melody is at first an exposition. It goes somewhere from somewhere. A melody takes us through time. [It] indicates its harmonic development… a good melody can be evocative. It can remind you of some place that you’ve been. And if a melody jars a memory, it serves a great purpose.”

Song Cycle, to this day, is famous for its abstract, stream-of-consciousness verbiage. But from that style he soon moved on to songs of clear content, and narrative grace. “I retired from that,” he explained, “but I still think it’s a valid idiom… I still have this iconoclastic, highly individual approach to songwriting. And I enjoy it very much. It’s an honor.”

Always brilliant with the use of physical symbols, he provided one of the best for the often rudderless navigation which songwriting demands. It came from his work scoring Popeye with Robert Altman, who was shooting an object on a boat from a boat. “There were no fixed points, you see. I feel very much like I am at sea” when writing songs.

“Songwriting is a matter of self-discovery,” he explained. “I don’t think a song should fall apart like a cheap watch on the street… it’s important to make a song a renewable resource. Something that can be listened to again.”

Timeless song has fortified his spirit: “Songs have a tremendous closeness to the soul. The psalms was my first all-time favorite in the Bible. I’ve always venerated a timeless, higher power.”

But how does one maintain a good attitude when the song isn’t coming? “I don’t get my knickers twisted,” he answered. “Composure is what it’s all about. But you must go there. You must make a habit of the luxury and the sanctuary that songwriting provides. You’re creating a world that you’re subject to… It’s transcendental, beyond possession. It really is.”

On the subject of these kinds of interviews with songwriters about songwriting, he said, “Everything is revealed, yet nothing is revealed. What is transferable is this sense of courage, of derring-do… This is infectious. And confirmational. It’s as helpful as belonging to some religious sect, to me. Hearing someone say, ‘Amen.’”

Our interview with him was conducted at his Hollywood home, where his wife Sally brought iced tea and took photos, and we watched as young lovers courted and kissed right outside his front window.